The War Between the States: Hardships Endured, 1861-1865

Hancock County, Ohio, Recruitment Poster

The attack by Confederate forces on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina on April 12, 1861, triggered the start of the American Civil War. Three days later, President Lincoln called on the states to field 75,000 volunteer troops for 90 days, and in early May he called for an additional 42,000 volunteers for a period of three years.

Small towns across Ohio responded to this national call. Even though Lincoln had requested 13,000 volunteers from Ohio, more than 30,000 crowded Ohioan recruiting stations. In August in Hancock County, 17-year-old Aaron Glathart enlisted as a private in a company formed at Findlay, being Company H, 57th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, First Brigade, Second Division, Fifteenth Corps, Army of the Tennessee, and was mustered in for three years service on December 12, 1861.[1]

Soon after enlistment Aaron was promoted to corporal for meritorious services, and for the same reason he was made sergeant in 1862.[2]

He was engaged in many battles, some of them the most notable of the war, including Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Siege of Corinth, Morning Sun, Tennessee, Wolf Creek Bridge, Tallahatchee, Holly Springs, Mississippi; Chickasaw Bayou, Yazoo Pass, Mississippi; Arkansas Post, Arkansas; second expedition to Chickasaw Bayou; Steele’s Bayou, Deer Creek, Mississippi; running the batteries at Vicksburg on the ram Queen of the West on April 16, 1863; Raymond, Mississippi; Jackson, Mississippi - the first and second battles; Champion Hills; Big Black River, Mississippi, May 17, 1863; Siege of Vicksburg, May 18 to July 4; Chattanooga; Missionary Ridge; Knoxville, Tennessee; Snake Creek Gap, Dalton, Resaca, Kingston, New Hope Church, Big Shanty, Kenesaw Mountain, Pumpkin Vine Creek and Atlanta, Georgia.

...[An] incident which showed his indomitable courage and pluck was when on May 19, 1863 [during the assault on Vicksburg, Mississippi], he was severely wounded in the abdomen. The wound was of a peculiar nature, a ball having pierced through twenty-seven thicknesses of his rubber blanket and a heavy brass belt plate, this ball and plate being now a dearly appreciated heir-loom in the family. He was immediately sent to the hospital, but on the same evening, he escaped the guards and crawled back to the battle field, accompanying his regiment on a forced march up the Yazoo.

However the wound did not heal and later became so serious that he was unable to carry a gun or wear a belt. He was assigned to light duty about camp, and was made camp postmaster. He positively refused to go to the hospital, preferring to stick to his regiment and take the fortunes of war as they came.[3]

In January 1864 the 57th Ohio Volunteer Infantry re-enlisted, being the first regiment to re-enlist as veterans in the 15th corps, and after a furlough home, was present at the beginning of the campaign against Atlanta.[3b] Records show Aaron re-enlisted as a veteran at Larkinsville, Alabama, January 1, 1864.[4]

Taken Prisoner

On July 19, 1864, the army of the Tennessee swung around Atlanta, and about 4 p.m. on the 22d, just after General McPherson was killed, he was captured and sent to Andersonville prison, where he was held from July 25 to October 1, 1864.[5]

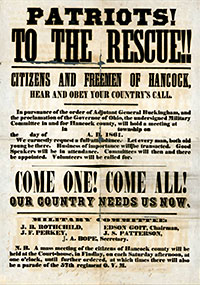

Andersonville prison, then known as Camp Sumter, was laid out in the customary style of Confederate prisons with sloping hills at each end and a small stream flowing between the hills. The prison was designed to house 10,000, but shoryly after Aaron's imprisonment, over 33,000 prisoners were being held there.

Camp Sumter, Andersonville, Georgia, color lithograph, 1890

The color lithograph above of Andersonville prison is deceptively benign. Approximately 19 ft (5.8 m) inside the inner stockade wall is a light fence known as "the dead line". It demarcated a no-man's land. Anyone crossing or even touching this "dead line" was shot without warning by sentries in the guard platforms, known as "pigeon roosts", which were roughly thirty yards apart on the inner stockade wall.[6]

The Confederate government was unable to provide the prisoners with adequate shelter, food, clothing, and medical care. The creek that ran through the compound was fetid, contributing to an epidemic-level rise in dysentery cases. Many prisoners lived in makeshift lean-to structures. Others had no shelter at all. The clothing of the men was miserable in the extreme. More than one-half were indecently exposed, and many were naked.[7]

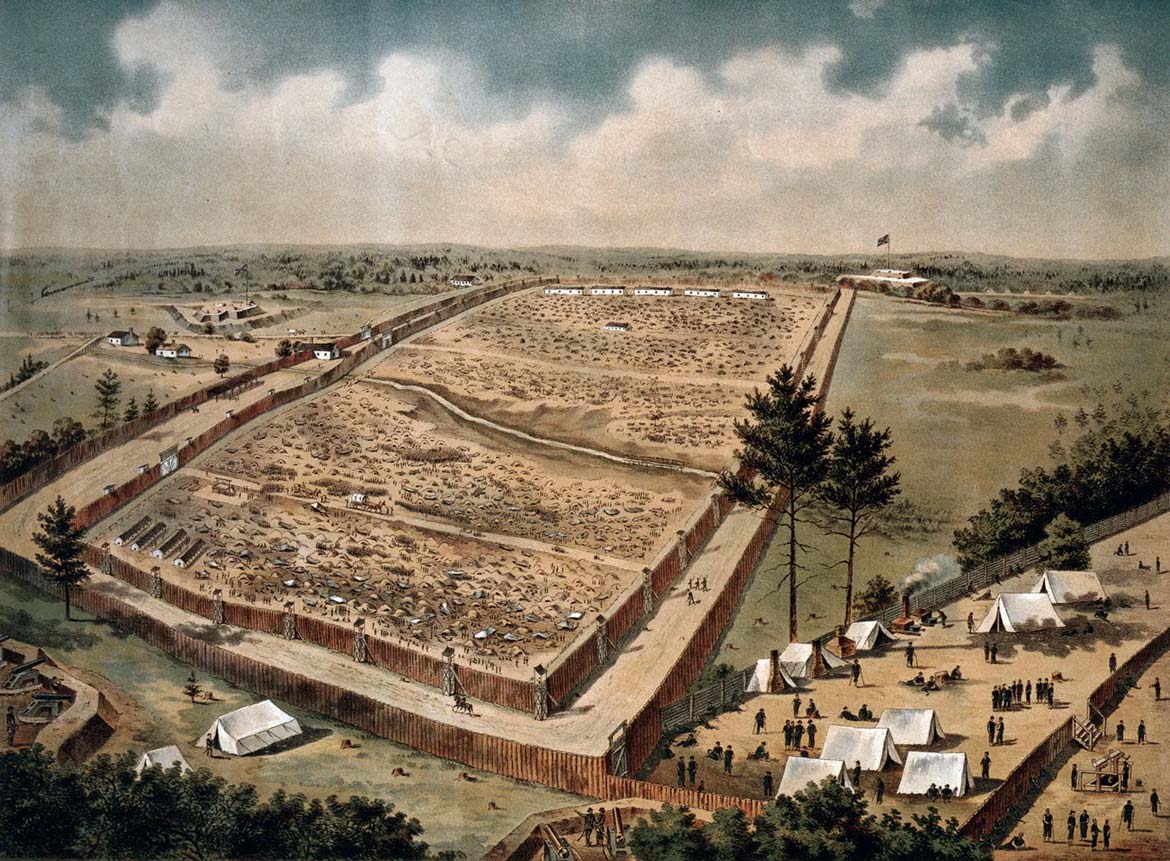

Andersonville Prison, Georgia, August 17, 1864. South east view of stockade

The wooden structure in the foreground is the latrine built right beside the stream where the men got their drinking water.[8]

During the summer of 1864 the prisoners suffered greatly from hunger, exposure, and disease. There was a high mortality rate, and a high incentive to escape.

Three times, while at Andersonville, he [Aaron] made his escape by tunneling out of his prison. Once he was free twenty-three days, and came within hearing of Sherman’s guns at Jonesboro, when he was re-captured by a planter with hounds.

Another time he and his comrades made a raft to float down Flint river. The first night the raft passed down the river in safety, but on the second night they were fired into, and crawled under the logs for safety, putting their heads far enough out of the water to breathe. The enemy came out to them in boats and took them prisoners. They were returned to Andersonville, and Mr. Glathart was tied up twelve hours by the thumbs by Wirtz [the commander of the prison].[9]

Somehow Aaron survived, and in the autumn of 1864 after William Tecumseh Sherman’s Union forces had captured Atlanta, all the prisoners who could be moved were sent to Millen, Georgia, and Florence, South Carolina.[10] Aaron was one of them.

He was...sent to Savannah and held about two weeks, and from there sent to Millen, Georgia, and held until about the first of December, when he was sent to Charleston, South Carolina, and there placed under the fire of the Federal batteries. His lucky star never deserted, or perhaps it would be more truthful to say his pluck never failed him, and after being held at Charleston three or four days he was sent to Florence, South Carolina, to a new stockade.[11]

Paroled

For both the North and the South, the burden of feeding and sheltering prisoners steadily increased as the war progressed. Early in the war, a system of parole and exchange was created and utilized extensively.[12]

He was paroled in the last part of December, 1864, and sent to the hospital at Annapolis. At that place he received a furlough and returned home in a very bad condition, being unable to speak aloud for seven months.

Flag of the 57th Ohio Volunteer InfantryBut he could not be contented to stay at home, and at great risk to himself he went to Richmond, Virginia, where he rejoined his regiment, and with it participated in the Grand Review at Washington, D.C. [in May 1865], filling his old position of color bearer, which he had held for the last fourteen months of his service, and carrying the battle scarred flag of his regiment.[13]

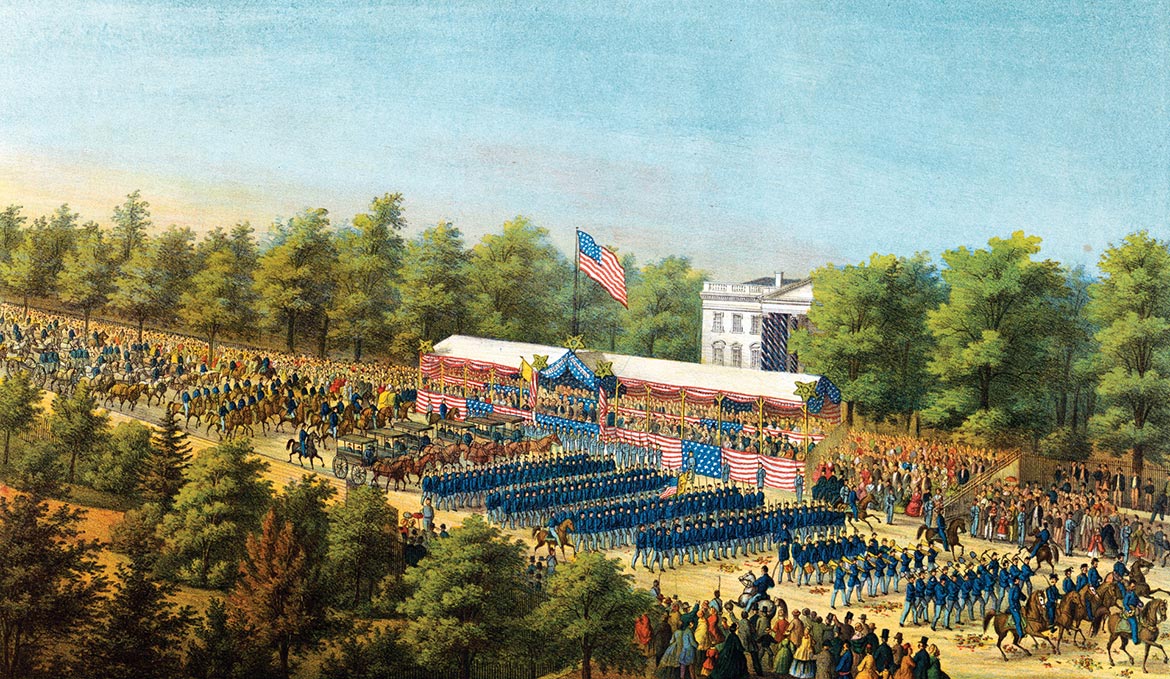

The Grand Review of the Armies, Washingnton DC, May 23-24, 1865

After weeks of mourning the death of Abraham Lincoln, the nation’s capital hosted a two-day Grand Review of its victorious armies.

Mustered Out

He was mustered out on August 25, 1865, at Little Rock, Arkansas, being at that time color bearer and postmaster of his regiment. He returned to Findlay broken in health, but remembering the healthy life of the western frontier and being inured to the outdoor life, he set resolutely to work to recover his health, and went to Kansas and camped on the prairie for three months.

He again went to Lawrence and went into the auctioneering and second-hand furniture business. A year later he bought a farm near Lawrence and remained there some six years, but his faith in Ohio had not wavered, and in 1874 he returned to his native county, where he farmed until 1897, when he retired and moved to Findlay....[14]

The Sacrifice of the Glathart Family

Three of Aaron's brothers died in the Civil War. The first was Manassa, who was a scout under General Lyons. He died aged 27 on August 23, 1861, of wounds received in action on August 10th at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri.[15] The next was Aaron's younger brother, Leon, who was a private in Company C, Forty-ninth Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He enlisted at Findlay in January 1864 and died the following month of smallpox at Chattanooga, Tennessee aged 18. Aaron's oldest brother, Rudolph, was killed, aged 37, on Brazos river, Texas, in May 1865 at the very end of the war, by guerrilla Confederates.[16]

Footnotes & Sources

- [1] (Anon.) A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (New York & Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1903), pp. 100-103. Note: Aaron was still alive at the time when his biography for this book was written.

- [2] Image of entry for Aaron J. Glathart in the Military and Personal Sketches of Ohio's Rank and File from Hancock County in the War of the Rebellion, from the Ohio Genealogical Society website and posted on ancestry.com.

- [3] A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (n 1).

- [3b] Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., American Civil War Regiments, 1861-1866 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999. The Union Army, vol. 2.

- [4] Military and Personal Sketches of Ohio's Rank and File from Hancock County in the War of the Rebellion (n 2).

- [5] A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (n 1).

- [6] History of the Andersonville Prison, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/camp_sumter_history.htm accessed 6 April 2023.

- [7] Michael E. Haskew, Prisons of the Civil War: An Enduring Controversy, Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/prisons-of-the-civil-war-an-enduring-controversy/, accessed 6 April 2023.

- [8] Sunken Eyes, Black Countenance: Life in Andersonville Prison video, Georgia Public Broadcasting, www.gpb.org/georgiastories/stories/andersonville_prison accessed 6 April 2023.

- [9] Military and Personal Sketches of Ohio's Rank and File from Hancock County in the War of the Rebellion (n 2).

- [10] www.britannica.com/place/Andersonville-Georgia, accessed 6 April 2023.

- [11] A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (n 1).

- [12] Haskew, (n 7).

- [13] A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (n 1).

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Graden, Debra, ed., Kansas Adjutant General Roll, Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 (Orem, UT: Ancestry, Inc., 1999.) This database is a transcription of the Kansas Adjutant General's Roll of Civil War Soldiers. Online www.ancestry.com database accessed 23 Nov 1999.

- [16] A Centennial Biographical History of Hancock County, Ohio (n 1).

Published 16 July 2023.